MARINERS VILLAGE: FACES OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

I moved to Mariner's Village in 1981, the day after an F-11 plane crashed two blocks away from our new home. My husband, toddler son and I dragged boxes through onlookers, military personnel and dogs sniffing out the plane's detritus.

I moved to Mariner's Village in 1981, the day after an F-11 plane crashed two blocks away from our new home. My husband, toddler son and I dragged boxes through onlookers, military personnel and dogs sniffing out the plane's detritus.

The Village offered us adequate housing for the first time in our shaky marriage, as well as a lawn and garden. Built in the l 940s for civilian workers at the navy yard, this "temporary housing" was first named Wentworth Acres, then Seacrest Village. Despite its reputation for transience, poverty and crime, I don't remember ever locking our door. The development provided affordable rents for generations of Portsmouth's working people even after local philanthropist Joseph Sawtelle purchased it.

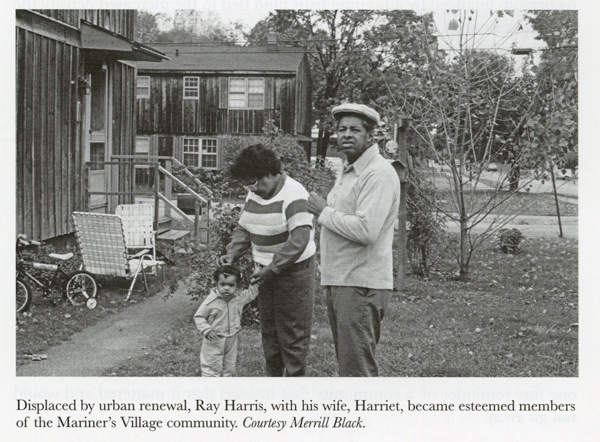

Puddle Dock families in the South End, displaced by urban renewal, took root there, as did students living on "College Row" and returning Vietnam veterans. Their Southeast Asian counterparts moved in after the war to work at a local fish-packing factory-another wave of refugees arriving at this Seacoast sanctuary.

When I moved there, half the residents had lived there for five years, a third for more than ten. Den ely populated and more diverse than any community in the state, the 722-unit development provided the growing city critical workforce housing, with almost 70 percent of Village residents employed in Portsmouth or within a ten-mile radius.

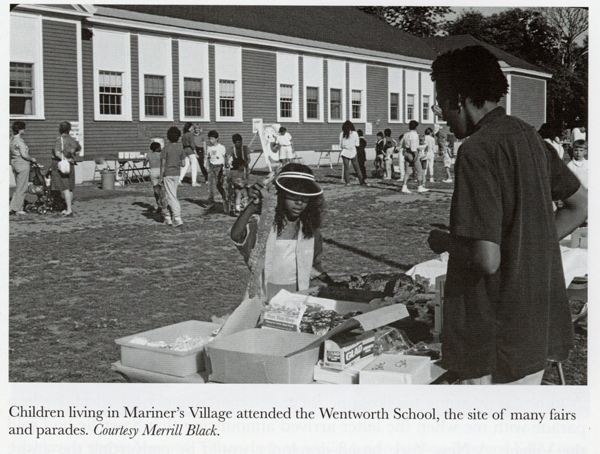

Yet Mariner's Village's dilapidated condition embarrassed the rapidly gentrifying port city. The Village's three street names-Circuit Road and Rockhill and Profile Avenues-showed up regularly in the local paper's police log. Yet many older residents remembered when the neighborhood school, Wentworth Elementary, carried the PTA banner for the greatest parent participation in the city; when the two pools were active and the buses still ran; when the neighborhood was a place you started out, not one where you ended up.

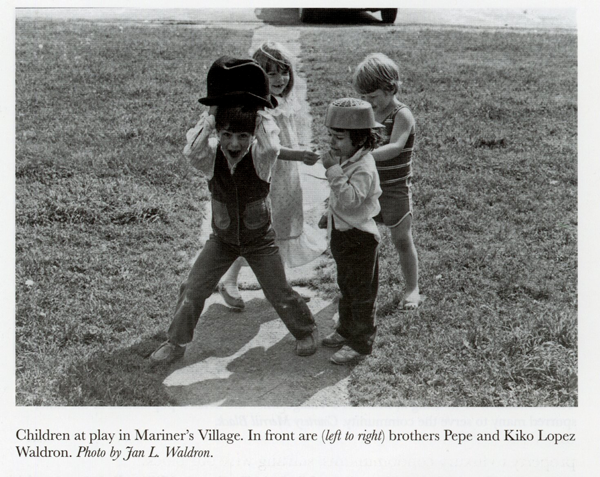

My marriage tanked within two years of our move. My four-year old son, Josh, and I planted lilies next to the porch and pansies around the laundry line, making shadow animals behind the billowing sheets. He built playhouses on the front lawn, and neighborhood kids came over to help.

Women on the block who still had husbands sent them over to shovel out my car all winter long. My neighbor Goodie would pad out in slippers and pajamas in all weather when my car wouldn't start to switch out my battery for a working one culled from the collection under his kitchen table.

I learned that teenagers had been smoking dope in my unlocked car and went to have it out with them. They hastily apologized. I turned, congratulating myself on my newfound assertiveness. The body builder from across the street was standing behind me, arms crossed. He'd followed me up the hill and had been there the whole time, watching my back.

My greatest support system was the problem-solving dyad of Jan and Lisa, who lived across from each other on Rockhill Avenue with their sons. Jan and I loved the word "betend," created by Josh. We used it often to envision the family lives we were building as single mothers. Bundling our boys into thriftshop snowsuits, we'd work our way into laughing fits. "Betend the car starts"; in the summer months, "Betend hamburger is on sale at Market Basket and we can make pizza and then go swimming"; "Betend we had child support."

We'd call on each other for emergencies: the returned angry father, the pet hamster loose in the walls, the birthday dust-up from too many kids and too little Carvel ice cream cake. And there was the perennial challenge: how to teach our boys to be good men.

We admired Ray Harris, whose garden at the end of Rockhill teemed with flowers, vegetables and grandchildren he and his wife, Harriet, cherished. A regular at the youth center near his house, Ray would always check on his neighbors and knew when the feral cats near the dumpster had kittens

needing homes.

Josh was planning his costume for the annual neighborhood Halloween parade with me when the letter arrived announcing that Sawtelle had soldthe Village. A New York-based developer would be converting the entire property to luxury condominiums, starting with our block.

I called Legal Aid, and attorneys Victoria Poulos and Elliot Berry met with concerned tenants at Alice Cyr's house up the hill. Widowed and elderly, Alice remembered the Village's glory days and was determined to stay put. During a well-attended meeting at Wentworth School the following week, residents formed Save Our Homes Organization (SOHO), a tenants' group to fight the displacement and remind Portsmouth of our community's value. We filed a successful class-action suit delaying the immediate displacement and the proposed radically raised rents.

Over the next three years, we attended city council meetings and organized demonstrations, voting drives and letter-writing campaigns. Ray Harris went with me to legislative hearings, wearing a suit and carrying his Bible to tell his story of moving north from West Virginia via Pease Air Force Base, owning a downtown gas station after the Korean War and losing his home in the South End to urban renewal.

A Concord-based organization, Women’s Education Resource Center, led by community organizers Gracia Berry and Becky Johnson, helped SOHO research a feasibility study supported by the city counsel and funded by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority. The study described the community and detailed alternatives including subsidized rents and ownership financed by a housing trust fund tied to the increased density the developer desired.

Annoyed by the tenants’ activism and the time the city took to grant concessions, the developer declared bankruptcy and abandoned the project. But those three years put faces on the issue of affordable housing. The struggle also offered mixed use housing models and partnerships the city still draws from. Osprey Landing, abutting the redeveloped Spinnaker Point Condominiums, still houses some original Mariner’s Village residents, and offers a percentage of below-market rentals, subsidized by local resources and the few remaining federal housing programs. Nonetheless, the chain link fence separating these rentals from the condominiums still stands.

These days, I drive through Spinnaker Point to the gym built by the original developer, now a city-run recreation center. Current condo rules preclude swing sets, laundry-lines, picnic tables and kiddie pools. There are almost no children evident anywhere. The City closed Wentworth School years ago.

The garden next to the tidy condo that was once my home still has day lilies. I always wonder if the bulbs we planted might have taken deep root, one tiny reminder of a community that insisted that it mattered and would not go away.